|

KEYBOARDS |

||||||||||||

|

The most used two-mallet grip is, in general, the same adopted for the snare drum and the timpani, with the difference that the fulcrum (i.e., the point of balance and of support) because of the different thickness of the handles, is moved slightly downward (fig. 8).

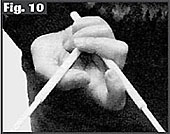

Another little difference lies in the fact that the mallet, while still starting out in its natural seat (the cavity of the palm of the hand), at times can come out towards the outside to favor the angle that, in any case, must be achieved by slightly widening the arms (fig. 9).

The basic four-mallet grips are:

Adopted by the famous vibraphonist and marimba player Lionel Hampton, the traditional jazz grip has been reevaluated and improved. In substance, it does not depart much from the independent mallet grips of today. In fact, the outside mallets are held between the middle and ring fingers while the inside ones are held between the index and middle finger, the palm flat towards the keyboard (fig. 12).

As we have already had an opportunity to say on other occasions, a technique is born and develops until it is established with the name of the one who conceived it (or who gets the credit for popularizing it). The grip with the palm vertical (fig. 13), adopted by many marimba players in the past, today is more known by the name of the one who had the merit of popularizing it, with suitable corrections; which is to say, the marimba player L. H. Stevens.

All the grips described so far have advantages and limitations because the complete grip doesn't exist, or hasn't been discovered yet. The best thing to do, in our opinion, consists in learning to make small modifications to your own basic grip depending on the performance needs. With this system, you will be able to exploit all the advantages of the various ways of holding the mallets. At the time, the basic four-mallet grip that we recommend is the one in which you will be best able to exploit the principal articulation movements and the independence of the fingers. Which is to say: outside mallets between the middle finger and the ring finger and inside mallets between thumb, index and middle finger, with the palm flat towards the keyboard. This, obviously, without renouncing other solutions such as, for example, changing to an intermediate or vertical grip (even with one hand), in the event these grips turn out to be technically more effective for what you have to play (fig. 14).

Six-mallet grips are still at an experimental stage, even if soloists have been trying to adopt them for about twenty years.

The famous English writer Anthony Hope has said: “Unless one is a genius, it is best to aim at being intelligible.” Following his advice, we are forced to explain in a simple and accessible manner, all the historical and didactic information that could help you judge and choose a good grip.

|